These days, Jovan Knutson wakes up when she’s ready. On her phone, she opens Wordle, a popular word puzzle game. She doesn’t leave bed until she has guessed the daily five-letter word or run out of tries. She usually gets it, and that makes her feel pretty good. Not too long ago, she had a tumor in an area of her brain responsible for language processing.

She exercises. A glioblastoma (GBM) diagnosis compelled Jovan to leave a demanding career in her mid-thirties, and she doesn’t miss sitting at a desk all day. The St. Paul, Minnesota resident climbs at a local gym and recently completed a 15K run. She’s an avid cyclist, and last year biked 100 miles in one day to the Mayo Clinic for an MRI. A few weeks later, she biked nearly 500 miles to visit family in Chicago.

She spends time with the people she loves. Jovan prepares meals like soups, salads and poke bowls, and she posts the mouth-watering results on Instagram. She savors the nightly routine of sharing dinner with her husband, Steve, while watching sports or a trending TV show. She meets her dad for lunch every week and makes extra time for her friends and younger siblings. Now, when she’s with someone, she’s really with them.

GBM led Jovan to reevaluate what is most important to her and prioritize her physical and mental well-being. She has found joy in the moment, and with it, a renewed sense of purpose and resilience.

“Little things that to most people probably seem mundane give me a feeling of love and joy and happiness,” she said. “I’ve gravitated toward those things and have now recreated my world to seek out those things.”

Jovan knew something was up when she started forgetting words and experienced difficulty writing emails. An Information Technology project manager, she considered herself a clear and precise communicator. A doctor suggested the symptoms were stress-related and told her to get more sleep.

Then, one summer morning while prepping for a backpacking trip, Jovan got an awful headache and sent a string of incoherent texts to her friend and hiking companion, who also happened to be an emergency medical technician. He urged Jovan to go to the emergency room, where a scan revealed a large brain tumor.

Everything moved quickly after that. Over the next few days, Jovan was admitted to the hospital, had a biopsy to confirm the tumor was cancerous and received a prognosis that devastated her. A neurosurgeon warned that she might lose the ability to talk and could face months of in-patient treatment.

Little things that to most people probably seem mundane give me a feeling of love and joy and happiness.—Jovan Knutson

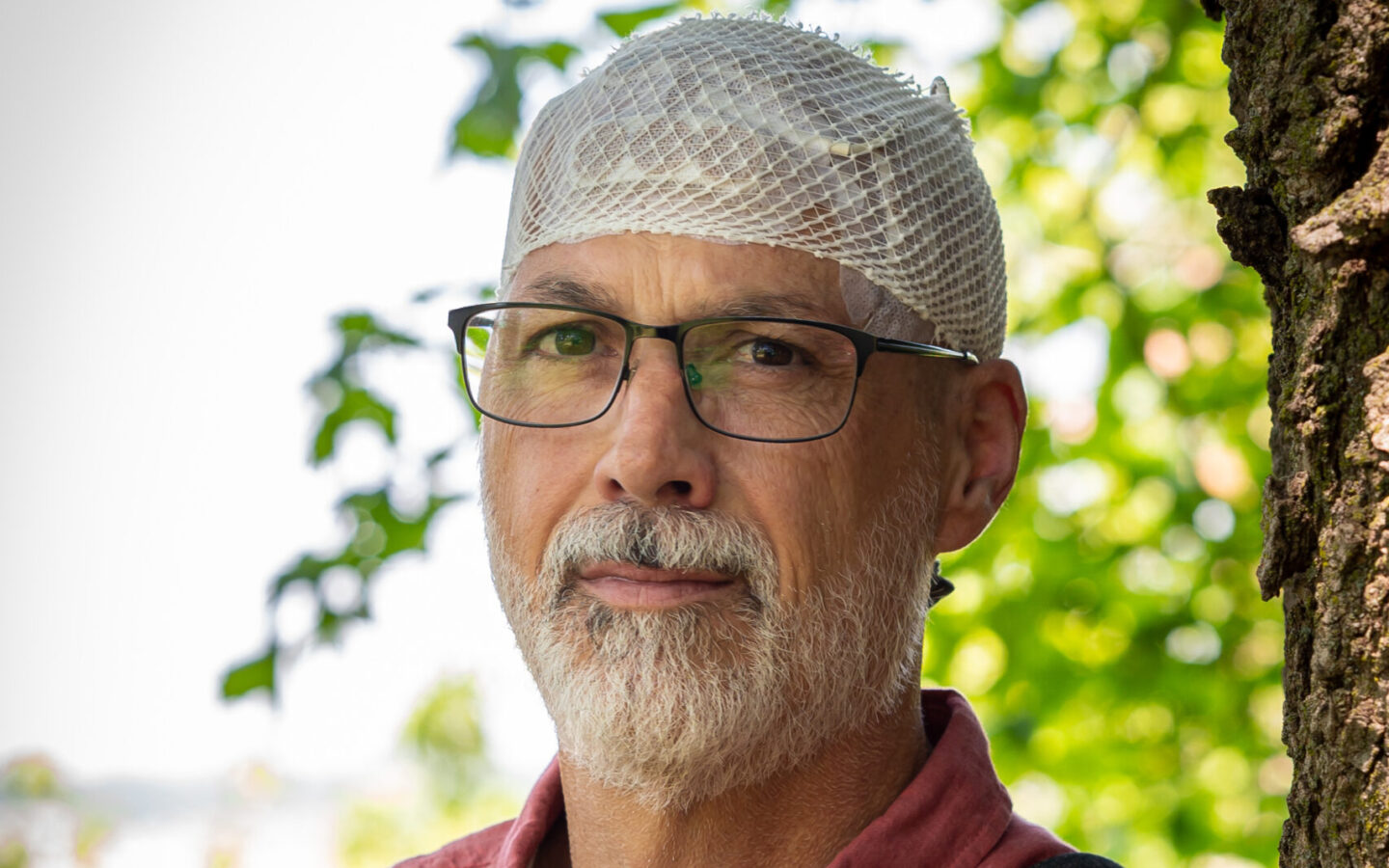

Jovan and Steve went to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota for a second opinion, and they ultimately decided to schedule a debulking procedure there. Surgery went as well as it could have. Her surgeon successfully removed as much of the tumor as possible, and Jovan’s speech was not impaired. Just two days later, she left the hospital and, with her doctor’s permission, went for a 5-mile walk with her husband, Steve. She then began various out-patient treatments.

Because of cancer’s impact on her focus and memory, Jovan did not return to work. She worried about losing something that had been so central to her identity.

A therapist encouraged Jovan to read “Man’s Search for Meaning” by Viktor Frankl, a psychiatrist’s memoir about surviving Nazi concentration camps during the Holocaust. The book discusses the importance of finding meaning in one’s life, particularly in difficult circumstances. Her therapist shared exercises based on the book to help Jovan identify what was most meaningful to her.

“I initially felt like I had to come up with a bucket list — I should go see Niagara Falls, I should go do all this other crazy stuff,” she said. “But when I really thought about how I wanted to spend my time, I kept going back to the things that actually are most important to me, like going outside, being with my family, cooking a good meal and watching some bad TV.”

Jovan also recognized she hadn’t derived much meaning from her job despite the time and energy she committed to it. She realized that, in all her striving, she hadn’t paid much attention to the here and now.

“In a way, basically retiring at age 35 was really freeing because I didn’t have to wait until I was much older to finally figure out what I’ve always wanted to do,” she said.

Jovan appreciates Steve’s persistent support during her cancer journey. He takes notes and asks incisive questions during her appointments, and he has helped manage all the administrative tasks that come with illness and work absence.

Steve said the first six months or so after Jovan’s diagnosis were tumultuous as they navigated the medical system and made difficult decisions foreign to most healthy young adults. But they’ve gained knowledge and hope as time has passed and the situation has improved.

“It has totally changed our lives top to bottom, but I’ve learned what really matters to both of us,” Steve said. “There are a lot of times where you get bogged down in the things that, at the end of the day, really don’t matter.”

Before her diagnosis, Jovan was an avid cyclist. A few months after her surgery, with her doctor’s permission, Steve got her a Peloton Bike so she could safely rebuild her strength and coordination. By the following spring, she felt confident enough to purchase a touring bike. Soon, she was going for rides longer than ever.

The 100-mile trip to the Mayo Clinic was her first “century ride,” and it included a harrowing stretch along steep gravel farm roads. With 70 miles already behind her, Jovan started telling herself, “Okay, make it to that next sign. Now make it to that next bend. Now…” She persevered and arrived in Rochester by nightfall. The next morning, her MRI showed no signs of recurrence.

“That ride is kind of how life has been for me,” she reflected later. “It’s taking things one day at a time, only thinking as far ahead as the next MRI. Hopefully, that next MRI shows all is good, and we enjoy the next stretch of days.”

Focusing on the present, Jovan says, has also helped her form closer relationships with friends and family.

“I just think about what’s happening right now, and it gives me an opportunity to really listen to my friends instead of going through a list of things I have to do and things I’m missing out on,” she said.

“I joke with my friends that, except for the cancer, I’m living my best life.”

The health status of patients featured reflects their condition at the time the story was written and photographs were taken and may have changed over time.